A new international study has developed a method for predicting the lifetime of mechanical equipment used in clean-energy systems. The research, led by Tohoku University and East China University of Science and Technology, is aimed at enhancing long-term performance and reducing material waste through better design.

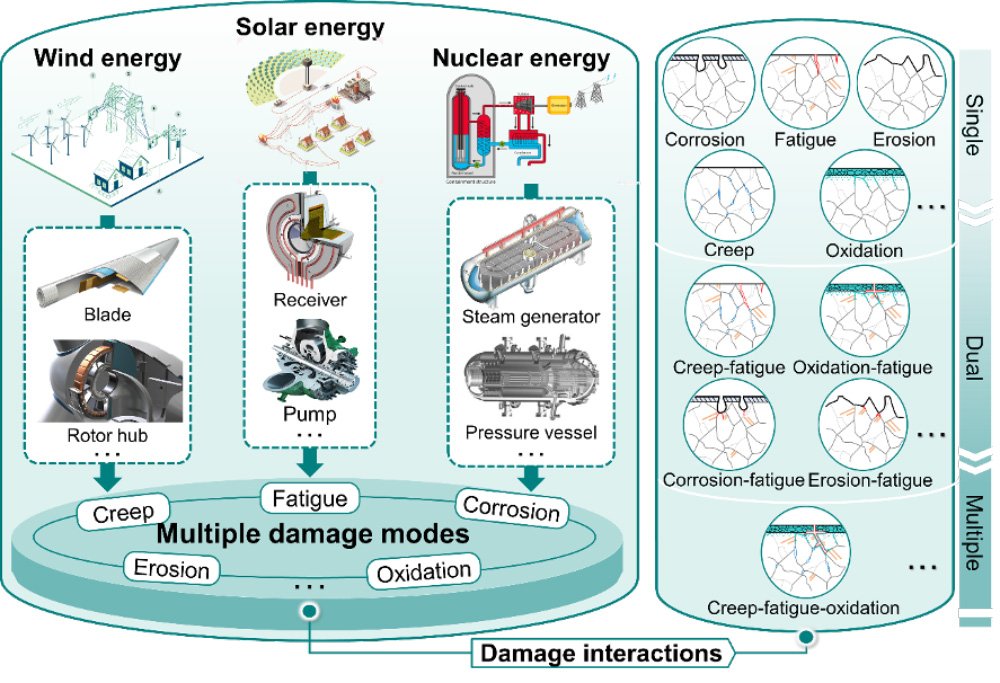

Technology, no matter how advanced, always comes with a shelf life. Mechanical equipment used in clean-energy systems is no different. But as global efforts toward carbon neutrality accelerate, assessing the durability of infrastructure such as wind turbines, solar power plants, and nuclear facilities has become increasingly important.

‘Clean-energy components often face damage from heat, stress, corrosion and other forces, which can combine in unpredictable ways, making it difficult for engineers to determine how long critical parts will last,’ said Run-Zi Wang, an assistant professor at Tohoku University’s Advanced Institute for Materials Research.

Traditionally, engineers have tried to circumvent this through increased ‘safety margins’, designing equipment to handle more stress than anticipated. But this sometimes wastes materials and can even create greater wear and tear.

‘Imagine the temperature drops and you put on five sweaters because you can’t predict how cold you may feel; this could lead to increased stress from being too hot and wearing too many clothes,’ said Wang.

Wang and his team developed a damage-driven lifetime design methodology that uses physics-informed models to track how equipment degrades under realistic conditions. The process can be compared to monitoring the wear of a bridge not only from traffic, but also from wind, temperature changes and moisture – factors that interact rather than act alone.

A case study on components exposed to high-temperature creep, fatigue and oxidation showed that the new method offers more consistent lifetime predictions than conventional models. The improved accuracy gives engineers clearer guidance on maintenance, design optimisation and long-term safety planning.

The study also highlights an important environmental connection. Extending the lifetime of clean-energy systems delays resource-intensive replacements and lowers total emissions across the entire lifecycle.

The researchers also outlined a three-level framework linking improved lifetime prediction to measurable reductions in carbon output. Depending on the type of equipment, the model suggests that net carbon-reduction benefits could increase significantly when this new methodology is applied.

To take into account different conditions across the globe, the team introduced a hierarchical Bayesian model that incorporates country-specific data, energy types and operational conditions. This probabilistic tool helps forecast environmental outcomes even in regions with limited monitoring systems.

‘This work shows that lifetime design can connect engineering decisions with environmental responsibility,’ summarised Wang. ‘By improving how we predict equipment performance, we can support clean-energy systems that are reliable and climate-conscious.’

The research also put forward the concept of a ‘full-chain technical tetrahedron’, linking lifetime design with materials science, manufacturing processes and equipment operations. Together, these elements offer a broad framework for designing next-generation clean-energy infrastructure that is dependable, efficient and aligned with global sustainability goals.

The research has been published in Engineering.