Researchers at the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland and the University of Seville in Spain have developed a method that allows a flapping-wing robot to land autonomously on a horizontal perch using a claw-like mechanism. The innovation could significantly expand the scope of robot-assisted tasks.

A bird landing on a branch makes the manoeuvre look like the easiest thing in the world, but in fact, the act of perching involves an extremely delicate balance of timing, high-impact forces, speed and precision. It’s a move so complex that no flapping-wing robot (ornithopter) has been able to master it, until now.

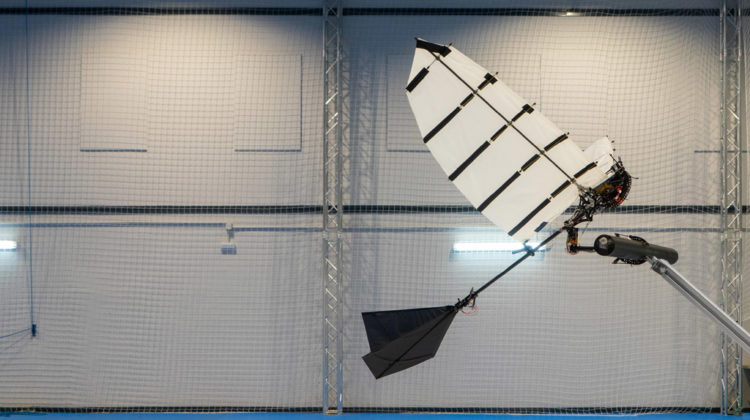

Raphael Zufferey, a postdoctoral fellow in the Laboratory of Intelligent Systems and Biorobotics lab in the School of Engineering built and tested the landing gear in collaboration with colleagues at the University of Seville, Spain, where the 700-gram ornithopter itself was developed as part of the European project GRIFFIN.

‘This is the first phase of a larger project,’ Zufferey said. ‘Once an ornithopter can master landing autonomously on a tree branch, then it has the potential to carry out specific tasks, such as unobtrusively collecting biological samples or measurements from a tree. Eventually, it could even land on artificial structures, which could open up further areas of application.’

He added that the ability to land on a perch could provide a more efficient way for ornithopters – which, like many unmanned aerial vehicles have limited battery life – to recharge using solar energy, potentially making them ideal for long-range missions. ‘This is a big step toward using flapping-wing robots, which as of now can really only do free flights, for manipulation tasks and other real-world applications,’ he said.

The engineering problems involved in landing an ornithopter on a perch without any external commands required managing many factors that nature has already so perfectly balanced. The ornithopter had to be able to slow down significantly as it perched, while still maintaining flight. The claw needed to be strong enough to grasp the perch and support the weight of the robot, without being so heavy that it couldn’t be held aloft. ‘That’s one reason we went with a single claw rather than two,’ Zufferey said. Finally, the robot needed to be able to perceive its environment and the perch in front of it in relation to its own position, speed and trajectory.

The researchers achieved all of this by equipping the ornithopter with an on-board computer and navigation system, which was complemented by an external motion-capture system to help it determine its position. The ornithopter’s leg-claw appendage was finely calibrated to compensate for the up-and-down oscillations of flight as it attempted to hone in on and grasp the perch. The claw itself was designed to absorb the robot’s forward momentum upon impact and to close quickly and firmly to support its weight. Once perched, the robot remains on the perch without energy expenditure.

Even with all of these factors to consider, Zufferey and his colleagues succeeded, ultimately building not just one but two claw-footed ornithopters to replicate their perching results.

Looking ahead, Zufferey is already thinking about how the device could be expanded and improved, especially in an outdoor setting. ‘At the moment, the flight experiments are carried out indoors, because we need to have a controlled flight zone with precise localisation from the motion capture system,’ he said. ‘In the future, we would like to increase the robot’s autonomy to perform perching and manipulation tasks outdoors in a more unpredictable environment.’

The research has been published in Nature Communications.