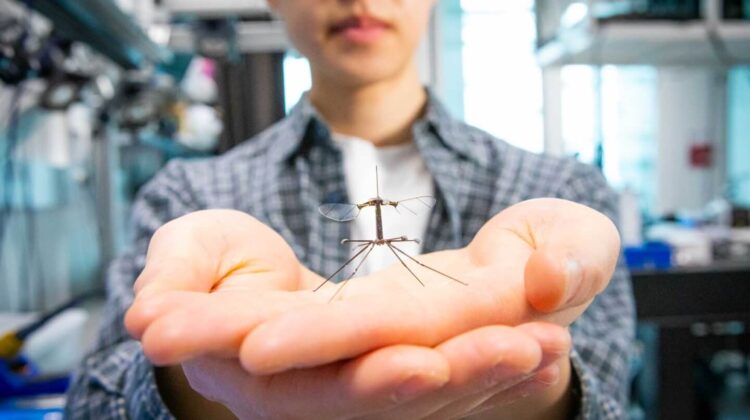

Engineers in Harvard University’s Microrobotics Laboratory have equipped their tiny RoboBee flying robot with new landing gear inspired by the graceful landings of crane flies.

The Harvard has long shown that it can fly, dive and hover like a real insect, and now it can land like one, too. The team led by Robert Wood, the Harry Lewis and Marlyn McGrath professor of engineering and applied sciences in the John A Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), has provided the robot with a set of long, jointed legs that help ease its transition from air to ground. The robot has also received an updated controller that helps it decelerate on approach, resulting in a gentle plop-down. These improvements protect the robot’s delicate piezoelectric actuators – energy-dense ‘muscles’ deployed for flight that are easily fractured by external forces from rough landings and collisions.

Landing has been problematic for the RoboBee due in part to how small and light it is – weighing just a tenth of a gram, with a wingspan of three centimetres. Previous iterations suffered from significant ground effect, or instability as a result of air vortices from its flapping wings – much like the groundward-facing full-force gales generated by helicopter propellers.

‘Previously, if we were to go in for a landing, we’d turn off the vehicle a little bit above the ground and just drop it, and pray that it would land upright and safely,’ explained Christian Chan, a graduate student who led the mechanical redesign of the robot.

The improvements to the robot’s controller, or brain, which enable it to adapt to the ground effects as it approaches, was led by former postdoctoral researcher Nak-seung Patrick Hyun, who led controlled landing tests on a leaf as well as rigid surfaces.

‘The successful landing of any flying vehicle relies on minimising the velocity as it approaches the surface before impact and dissipating energy quickly after the impact,’ said Hyun, who is now an assistant professor at Purdue University. ‘Even with the tiny wing flaps of RoboBee, the ground effect is non-negligible when flying close to the surface, and things can get worse after the impact as it bounces and tumbles.’

The lab looked to nature to inspire mechanical upgrades for skilful flight and graceful landing on a variety of terrains. They chose the crane fly, a relatively slow-moving, harmless insect that emerges from spring to autumn and is often mistaken for a giant mosquito. ‘The size and scale of our platform’s wingspan and body size was fairly similar to crane flies,’ Chan said.

They noted crane flies’ long, jointed appendages, which most likely give the insects the ability to dampen their landings. Crane flies are further characterised by their short-duration flights – much of their brief adult lifespan (days to a couple weeks) is spent landing and taking off.

Considering specimen records from Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology database, the team created prototypes of different leg architectures, settling on designs similar to a crane fly’s leg segmentation and joint location. The lab used manufacturing methods pioneered in the Harvard Microrobotics Lab for adapting the stiffness and damping of each joint.

Postdoctoral researcher Alyssa Hernandez brought her biology expertise to the project, having received a PhD from Harvard’s Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, where she studied insect locomotion. ‘RoboBee is an excellent platform to explore the interface of biology and robotics,’ Hernandez said. ‘Seeking bioinspiration within the amazing diversity of insects offers us countless avenues to continue improving the robot. Reciprocally, we can use these robotic platforms as tools for biological research, producing studies that test biomechanical hypotheses.’

Currently the RoboBee stays tethered to off-board control systems. The team will continue to focus on scaling up the vehicle and incorporating onboard electronics to give the robot sensor, power and control autonomy – a three-pronged holy grail that would allow the RoboBee platform to truly take off.

‘The longer-term goal is full autonomy, but in the interim, we have been working through challenges for electrical and mechanical components using tethered devices,’ said Wood. ‘The safety tethers were, unsurprisingly, getting in the way of our experiments, and so safe landing is one critical step to remove those tethers.’

The RoboBee’s diminutive size and insect-like flight prowess offer intriguing possibilities for future applications, including environmental monitoring and disaster surveillance. Among Chan’s favourite potential applications is artificial pollination – picture swarms of RoboBees buzzing around vertical farms and gardens of the future.

The research has been published in Science Robotics.