A team of UCLA engineers and their colleagues have developed a new design strategy and 3D-printing technique that enables them to build robots in a single step.

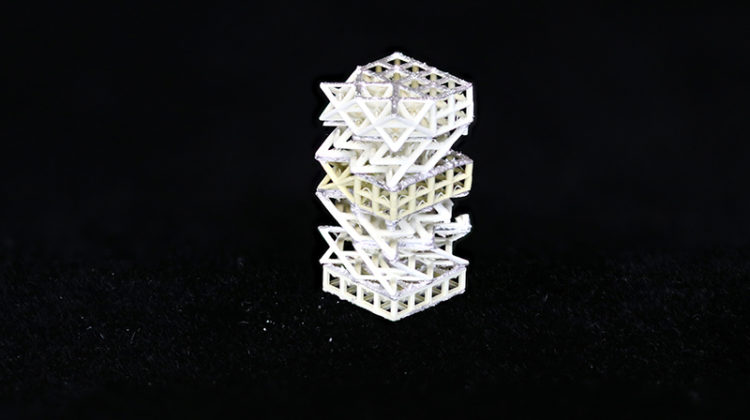

The breakthrough enabled the entire mechanical and electronic systems needed to operate a robot to be manufactured all at once using a new 3D-printing process for engineered active materials with multiple functions, known as metamaterials. Once printed, the ‘meta-bots’ are capable of propulsion, movement, sensing and decision-making.

The printed metamaterials consist of an internal network of sensory, moving and structural elements, and can move by themselves following programmed commands. With the internal network of moving and sensing already in place, the only external component needed is a small battery to power the robot.

‘We envision that this design and printing methodology of smart robotic materials will help realise a class of autonomous materials that could replace the current complex assembly process for making a robot,’ said the study’s principal investigator, Xiaoyu (Rayne) Zheng, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering, and of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the UCLA Samueli School of Engineering. ‘With complex motions, multiple modes of sensing and programmable decision-making abilities all tightly integrated. It’s similar to a biological system with the nerves, bones and tendons working in tandem to execute controlled motions.’

The team demonstrated the integration with an on-board battery and controller for the fully autonomous operation of the 3D-printed robots – each of which is the size of a fingernail. According to Zheng, the methodology could lead to new designs for biomedical robots, such as self-steering endoscopes or tiny swimming robots that can emit ultrasound and navigate themselves near blood vessels to deliver drugs to specific sites inside the body.

The meta-bots could also potentially be used to explore hazardous environments. In a collapsed building, for example, a swarm of such tiny robots armed with integrated sensing parts could quickly gain access to confined spaces, assess threat levels and help rescue efforts by finding people trapped in the rubble.

Robots, no matter their size, are typically built in a series of complex manufacturing steps that integrate the limbs and electronic and active components. The process results in robots that are heavier, bulkier and have reduced force output compared to those that could be built using this new method.

The key in the UCLA-led, all-in-one method is the design and printing of piezoelectric metamaterials – a class of intricate lattice materials that can change shape and move in response to an electric field or create an electrical charge as a result of physical forces.

The use of active materials that can translate electricity into motion isn’t new. However, these materials generally have limits in their range of motion and distance of travel. They also need to be connected to gearbox-like transmission systems in order to achieve desired motions.

In contrast, the UCLA-developed robotic materials – each of which is the size of a penny – are composed of intricate piezoelectric and structural elements that are designed to bend, flex, twist, rotate, expand or contract at high speeds.

‘This allows actuating elements to be arranged precisely throughout the robot for fast, complex and extended movements on various types of terrain,’ said the study’s lead author, Huachen Cui, a UCLA postdoctoral scholar in Zheng’s Additive Manufacturing and Metamaterials Laboratory. ‘With the two-way piezoelectric effect, the robotic materials can also self-sense their contortions, detect obstacles via echoes and ultrasound emissions, as well as respond to external stimuli through a feedback control loop that determines how the robots move, how fast they move and toward which target they move.’

The team also presented a methodology to design these robotic materials so that users could make their own models and print the materials into a robot directly.

Using the technique, the team built and demonstrated three ‘meta-bots’ with different capabilities. One robot can navigate around S-shaped corners and randomly placed obstacles, another can escape in response to a contact impact, while the third robot could walk over rough terrain and even make small jumps.

The research has been published in Science.