Materials engineers at Stanford University in California have 3D-printed tens of thousands of a difficult-to-manufacture type of nanoparticle that has been long predicted to yield promising new materials that can change form in an instant.

In nanomaterials, shape is destiny. That is, the geometry of the particles in the material defines the material’s physical characteristics.

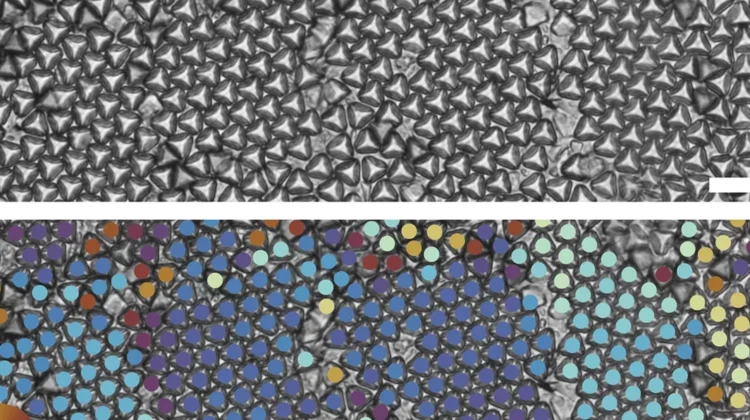

‘A crystal made of nano-ball bearings will arrange themselves differently than a crystal made of nano-dice and these arrangements will produce very different physical properties,’ said Wendy Gu, an assistant professor of mechanical engineering at Stanford University. ‘We’ve used a 3D-nanoprinting technique to produce one of the most promising shapes known – Archimedean truncated tetrahedrons. They are micron-scale tetrahedrons with the tips lopped off.’

The researchers nanoprinted tens of thousands of these challenging nanoparticles, stirred them into a solution and then watched as they self-assembled into various promising crystal structures. More critically, these materials can shift between states in minutes, simply by rearranging the particles into new geometric patterns.

This ability to change ‘phases,’ as materials engineers refer to this shapeshifting quality, is similar to the atomic rearrangement that turns iron into tempered steel, or in materials that allow computers to store data in digital form.

‘If we can learn to control these phase shifts in materials made of these Archimedean truncated tetrahedrons it could lead in many promising engineering directions,’ Gu said.

It has long been theorised that Archimedean truncated tetrahedrons (ATTs) are among the most desirable of geometries for producing materials that can easily change phase, but until recently, they were challenging to fabricate. Gu is quick to point out that her team isn’t the first to produce nanoscale ATTs in quantity, but they are among the first, if not the first, to use 3D nanoprinting to do it.

‘With 3D nanoprinting, we can make almost any shape we want. We can control the particle shape very carefully,’ Gu explained. ‘This particular shape has been predicted by simulations to form very interesting structures. When you can pack them together in various ways they produce valuable physical properties.’

ATTs form at least two highly desirable geometric structures. The first is a hexagonal pattern in which the tetrahedrons rest flat on the substrate with their truncated tips pointing upward like a nanoscale mountain range. The second is perhaps even more promising, Gu said. It is a crystalline quasi-diamond structure in which the tetrahedrons alternate in upward- and downward-facing orientations, like eggs resting in an egg carton. The diamond arrangement is considered a ‘Holy Grail’ in the photonics community and could lead in many new and interesting scientific directions.

Most importantly, however, when properly engineered, future materials made of 3D-printed particles can be rearranged rapidly, switching easily back and forth between phases with the application of a magnetic field, electric current, heat, or other engineering method.

Gu said she can imagine coatings for solar panels that change throughout the day to maximise energy efficiency, new-age hydrophobic films for airplane wings and windows that mean they never fog or ice up, or new types of computer memory. The list goes on.

‘Right now, we’re working on making these particles magnetic to control how they behave,’ Gu said. ‘The possibilities are only beginning to be explored.’

The research has been published in Nature Communications.