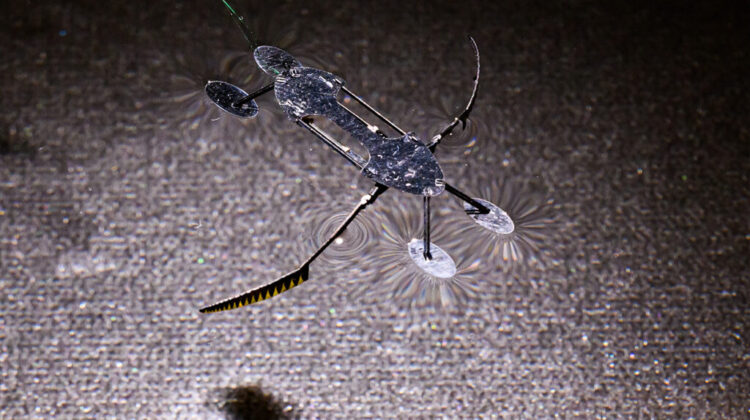

Researchers at Washington State University have developed two insect-like robots – mimicking a mini-bug and a water strider – that they say are the smallest, lightest and fastest fully functional micro-robots ever known to have been created.

The mini-bug weighs in at eight milligrams, while the water strider weighs 55 milligrams. Both can move at about six millimetres a second. ‘That is fast compared to other micro-robots at this scale, although it still lags behind their biological relatives,’ said Conor Trygstad, a PhD student in the School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering. An ant typically weighs up to five milligrams and can move at almost a metre per second.

According to the researchers, miniature robots such as these could one day be used for work in areas such as artificial pollination, search and rescue, environmental monitoring, micro-fabrication or robotic-assisted surgery.

The key to the tiny robots is the tiny actuators that make them move. Trygstad used a new fabrication technique to miniaturise the actuator down to less than a milligram, the smallest ever known to have been made.

‘The actuators are the smallest and fastest ever developed for micro-robotics,’ said Néstor O Pérez-Arancibia, Flaherty associate professor in engineering at WSU’s School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering.

The actuator uses a material called a shape memory alloy that’s able to change shapes when it’s heated. It’s called ‘shape memory’ because it remembers and then returns to its original shape. Unlike a typical motor that would move a robot, these alloys don’t have any moving parts or spinning components.

‘They’re very mechanically sound,’ said Trygstad. ‘The development of the very lightweight actuator opens up new realms in micro-robotics.’

Shape memory alloys aren’t generally used for large-scale robotic movement because they’re too slow. In the case of the WSU robots, however, the actuators are made of two tiny shape memory alloy wires that are about 0.02 millimetres in diameter. With a small amount of current, the wires can be heated up and cooled easily, allowing the robots to flap their fins or move their feet at up to 40 times per second. In preliminary tests, the actuator was also able to lift more than 150 times its own weight.

Compared to other technologies used to make robots move, the shape memory alloy technology also requires only a very small amount of electricity or heat to make them move. ‘The shape memory alloy systems require a lot less sophisticated systems to power them,’ said Trygstad.

Trygstad, an avid fly fisherman, has long observed water striders and would like to further study their movements. While the WSU water strider robot does a flat flapping motion to move itself, the natural insect does a more efficient rowing motion with its legs, which is one of the reasons that the real thing can move much faster.

The researchers would like to copy another insect and develop a water-strider-type robot that can move across the top of the water surface as well as just under it. They are also working to use tiny batteries or catalytic combustion to make their robots fully autonomous and untethered from a power supply.