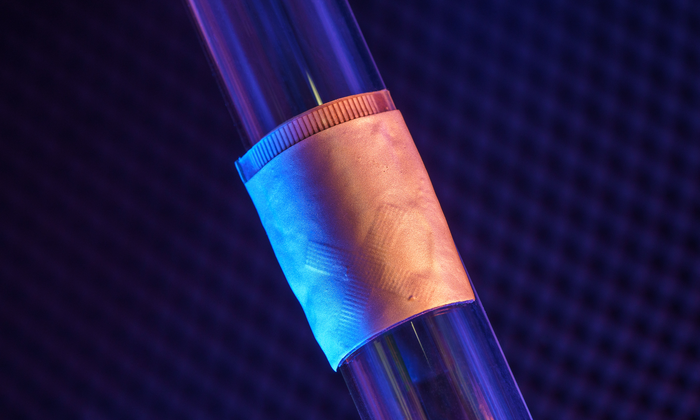

A team of engineers and doctors at the University of California San Diego has developed a wearable ultrasound device that can assess both the structure and function of the human heart. Crucially, the portable device, which is roughly the size of a postage stamp, can be worn for up to 24 hours and works even during strenuous exercise; issues with heart function often manifest only when the body is in motion.

According to Sheng Xu, a professor of nanoengineering, the team’s goal is to make ultrasound more accessible to a larger population. Currently, echocardiograms – ultrasound examinations for the heart – require highly trained technicians and bulky devices. ‘The technology enables anybody to use ultrasound imaging on the go,’ Xu said. ‘By providing patients and doctors with more thorough details, continuous and real-time cardiac image monitoring is poised to fundamentally optimise and reshape the paradigm of cardiac diagnoses.’

Thanks to custom AI algorithms, the device is capable of measuring how much blood the heart is pumping in real time, which is important because most cardiovascular diseases stem from the heart not pumping enough blood. It uses ultrasound to continuously capture images of the heart’s four chambers from different angles and automatically analyses a clinically relevant subset of the images in real time using custom-built AI technology. The resulting images have high spatial resolution, temporal resolution and contrast.

The sensor’s unique design makes it ideal for bodies in motion. ‘The device can be attached to the chest with minimal constraint to the subjects’ movement, even providing a continuous recording of cardiac activities before, during and after exercise,’ said postdoctoral researcher Xiaoxiang Gao.

The system gathers information through a stretchable patch as soft as human skin, designed for optimal adherence. The patch sends and receives the ultrasound waves, which are used to generate a constant stream of images of the structure of the heart in real time.

The system can examine the left ventricle of the heart in separate bi-plane views using ultrasound, generating more clinically useful images than were previously available. As a use case, the team demonstrated imaging of the heart during exercise, which is not possible with the rigid, cumbersome equipment used in clinical settings.

Xu’s team developed an algorithm to facilitate continuous, AI-assisted automatic processing. ‘A deep-learning model automatically segments the shape of the left ventricle from the continuous image recording, extracting its volume frame-by-frame and yielding waveforms to measure stroke volume [the volume of blood the heart pumps out with each beat], cardiac output [the volume of blood the heart pumps out every minute] and ejection fraction [the percentage of blood pumped out of the left ventricle of the heart with each beat],’ said Master’s student Mohan Li.

‘Specifically, the AI component involves a deep-learning model for image segmentation, an algorithm for heart volume calculation and a data-imputation algorithm,’ said Master’s student Ruixiang Qi. ‘We use this machine-learning model to calculate the heart volume based on the shape and area of the left ventricle segmentation. The imaging-segmentation deep-learning model is the first to be functionalised in wearable ultrasound devices. It enables the device to provide accurate and continuous waveforms of key cardiac indices in different physical states, including static and after exercise, which has never been achieved before.’

Thus, the technology can generate curves of the three indices continuously and non-invasively, as the AI component processes the continuous stream of images to generate numbers and curves.

To create the platform, the team faced some technical challenges that required careful decision-making. To produce the wearable device itself, the researchers used a piezoelectric 1-3 composite bonded with Ag-epoxy backing as the material for transducers in the ultrasound imager, reducing risk and improving efficiency over previous methods. When choosing the transmission configuration of the transducer array, they achieved superior results through wide-beam compounding transmission. They also selected from nine popular models for the machine-learning-based image segmentation, landing on FCN-32, which achieved the highest possible accuracy.

In the current iteration, the patch must be connected to a computer, but he team has developed a wireless circuit that will be covered in a forthcoming publication.

The research has been published in Nature.