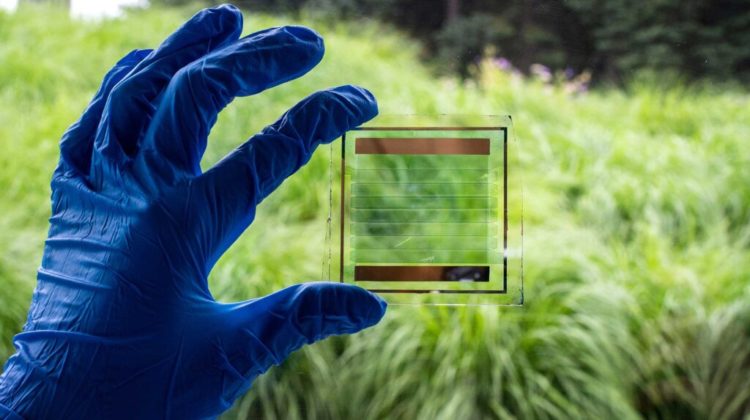

Researchers at the University of Michigan have developed a way to manufacture their highly efficient and semi-transparent solar cells, an important step toward bringing transparent solar cells to home windows.

‘In principle, we can now scale semi-transparent organic solar cells to two metres by two metres, which brings our windows much closer to reality,’ said Stephen Forrest, the Peter A Franken distinguished university professor of electrical engineering.

Traditional silicon-based solar cells are completely opaque, which works for solar farms and roofs but defeats the purpose of windows. However, organic solar cells, in which the light absorber is a type of plastic, can be transparent.

Organic solar cells have lagged behind their silicon-based cousins for energy-producing purposes due to a number of engineering challenges, including low efficiency and short lifespans. But recent work in Forrest’s lab has achieved record efficiencies of ten per cent and estimated lifetimes of up to 30 years.

The team has now turned its attention to making transparent solar cells manufacturable. A significant challenge is creating the micron-scale electrical connections between individual cells that comprise the solar module. Conventional methods that use lasers to pattern the cells can easily damage the organic light absorbers.

Instead, the team developed a multi-step peel-off patterning method that achieved micron-scale resolution. They deposited thin films of plastic and patterned them into extremely thin strips. Then, they set down the organic and metal layers. Next, they peeled off the strips, creating very fine electrical interconnections between the cells.

The group connected eight semi-transparent solar cells, each four centimetres long by 0.4 centimetres wide separated by 200 micrometre-wide interconnections, to create a single 13 square centimetre module. The power conversion efficiency of 7.3 per cent was about ten per cent less than for the individual solar cells in the module. This small efficiency loss doesn’t increase with the size of the module; hence, similar efficiencies are expected for metre-scale panels.

With a transparency nearing 50 per cent and a greenish tint, the cells are suitable for use in commercial windows. The higher transparencies that are likely to be preferred for the residential market are easily achieved by this same technology.

‘It is now time to get industry involved to turn this technology into affordable applications,’ said Xinjing Huang, a U-M doctoral student in applied physics.

Eventually, the flexible solar cell panel will be sandwiched between two window panes. The goal for these energy-generating window films is to be about 50 per cent transparent with 10–15 per cent efficiency. Forrest believes that this could be achieved within a couple years.

‘The research that we are doing is de-risking the technology so that manufacturers can make the investments needed to enter large scale production,’ Forrest said.

The technique can also be generalised to other organic electronic devices, he said. And his group is already applying it to OLEDs for white lighting.

The University of Michigan has applied for patent protection and is now seeking partners to bring the technology to market.

The research has been published in Joule.