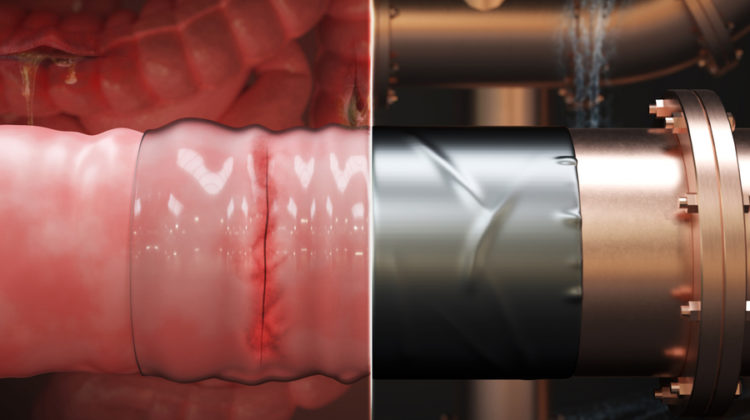

A team of engineers at MIT, the Mayo Clinic and the Southern University of Science and Technology has developed a strong, flexible, and biocompatible sticky patch that can be easily and quickly applied to biological tissues and organs to help seal tears and wounds – effectively surgical duct tape. Like duct tape, the new patch is sticky on one side and smooth on the other. In its current formulation, the adhesive is designed to seal defects in the gastrointestinal tract.

According to the team, the surgical sticky patch could one day be stocked in operating rooms and used as a fast and safe alternative or reinforcement to hand-sewn sutures to repair leaks and tears in the gut and other biological tissues.

In a series of experiments, the researchers demonstrated that the patch can be quickly stuck to large tears and punctures in the colon, stomach and intestines of different types of animal. The adhesive binds strongly to tissues within several seconds and will stay in place for more than a month. It’s also flexible, capable of expanding and contracting with a functioning organ as it heals. Once the injury has completely healed, the patch gradually degrades without causing inflammation or sticking to surrounding tissues.

‘We think this surgical tape is a good base technology to be made into an actual, off-the-shelf product,’ said Hyunwoo Yuk, a research scientist in MIT’s Department of Mechanical Engineering. ‘Surgeons could use it as they use duct tape in the nonsurgical world. It doesn’t need any preparation or prior step. Just take it out, open and use.’

The new surgical duct tape builds on the team’s 2019 design for a double-sided tape, which comprised a single layer that was sticky on both sides. Designed to join two wet surfaces together, the tape featured an adhesive made from polyacrylic acid, an absorbent material found in nappies, which starts out dry and absorb moisture when it comes into contact with a wet surface or tissue, temporarily sticking to the tissue in the process. Mixed into the material were so-called NHS esters, which can bind with proteins in the tissue to form stronger bonds, and an adhesive with gelatine or chitosan — natural ingredients that kept the tape’s shape.

Although the double-sided tape strongly bonded different tissues together, consultations with surgeons suggested that a single-sided version would be more useful. ‘In practical situations, it’s not common to have to stick two tissues together – organs need to be separate from each other,’ said MIT postdoc Jingjing Wu. ‘One suggestion was to use this sticky element to repair leaks and defects in the gut.’

Surgeons typically repair leaks and tears in the gastrointestinal tract with surgical sutures, but sewing the stitches requires precision and training, and following surgery, the sutures can trigger scarring. The tissue between stitches could also tear, causing secondary leakages that could lead to sepsis.

‘We thought, maybe we could turn our sticky element into a product to repair gut leaks, similar to sealing pipes with duct tape,’ Wu said. ‘That pushed us toward something more like single-sided tape.’

The researchers first changed their adhesive recipe, replacing gelatine and chitosan with a longer-lasting hydrogel – in this case, polyvinyl alcohol. This kept the adhesive physically stable for more than a month – long enough for a typical gut injury to heal. They also added a second, non-sticky top layer made from a biodegradable polyurethane that has about the same stretch and stiffness of natural gut tissue in order to keep the patch from adhering to the surrounding tissue.

‘We don’t want the patch to be weaker than tissue because otherwise it would risk bursting,’ Yuk said. ‘We also don’t want it to be stiffer because it would restrict the peristaltic movement in guts that is essential for digestion.’

The researchers found that although the new patch stuck to tissues, it also swelled, just as a fully wet, hydrogel-based nappy would, causing the tape and the underlying tear it was intended to seal to stretch. ‘It was almost an impossible problem because hydrogel naturally swells,’ said Yuk. ‘But we did a simple trick: we pre-stretched the adhesive layer a bit, then introduced the non-adhesive layer, so that when applied to a tissue, the pre-stretching cancels out the swelling.’

When they applied the patch to defects in the colons and stomachs of rats, they found that it maintained a strong bond as the injuries fully healed. It also produced minimal scarring and inflammation compared with repairs made with conventional sutures. And when it was applied over colon defects in pigs, the defects fully healed with no sign of secondary leakage.

Yuk and Zhao are now developing the adhesive through a new start-up and hope to pursue FDA approval to test the patch in a medical setting.

‘There are millions of surgeries worldwide a year to repair gastrointestinal defects and the leakage rate is up to 20 per cent in high-risk patients,’ Zhao said. ‘This tape could solve that problem and potentially save thousands of lives.’

The research has been published in Science Translational Medicine.