A team of engineers from the University of Pennsylvania have designed a soft material with potential applications in robotics, medical devices and wearable technologies that is both tear-resistant and able to resist deformation.

In engineering, traditional soft materials are either tough – that is, difficult to tear – or stiff, meaning that they are able to resist deformation. The trade-offs that come with these two properties make it difficult to design a material that’s both.

Previous approaches have involved combining two types of materials, alternating the placement of rigid and flexible materials throughout a final composite material to help prevent and slow down the formation of tears. However, manufacturing a product made from multiple material types increases the cost and slows production time, as it requires investment in creating chemical compatibility between the two materials to allow them to stick together.

In order to create material that’s both soft and tough, the University of Pennsylvania engineers took inspiration from the way muscle fibres are aligned in the human heart. In an average human lifespan, the heart beats more than two billion times. The aorta’s tissue is strong enough to withstand this stress, yet flexible enough to maintain a steady flow of blood.

‘The answer to many problems in nature is spatial variation,’ said Jordan Raney, assistant professor in mechanical engineering and applied mechanics in Penn’s School of Engineering and Applied Science. ‘Tissues are made up of features with varying patterns and degrees of order, and this heterogeneity of the structure allows it to perform multiple functions simultaneously. In engineering soft materials, you can either create heterogeneity by employing multiple material types or by changing a few aspects of one type of material, such as fibre alignment. Our approach is the latter.’

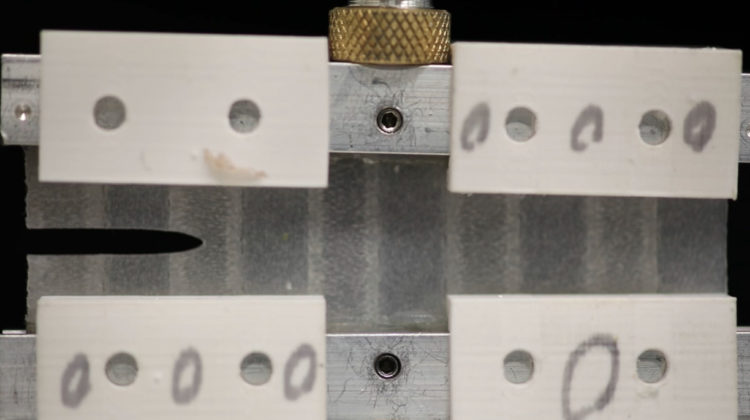

The researchers mimicked this variation by adding glass fibres to polydimethylsiloxane, a type of soft silicone. Crucially, they manipulated the angle at which the glass fibres were embedded in silicone as the material emerged from a 3D-printing nozzle. The embedded glass fibres provided the soft silicone with structural fibres akin to collagen in skin.

‘Here we created a simple tear-resistant material by just manipulating the fibre alignment,’ saidChengyang Mo, a graduate student in Raney’s lab. ‘We were able to slow the tear and we can easily manipulate the number of stripes to attune the material to different applications where it might need flexibility over toughness or vice versa. But we didn’t stop there. We wanted to improve these properties further and that’s when we looked at the aorta.”

The research has been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.