A team of researchers from Aalto University in Espoo, Finland, and the University of Cambridge has demonstrated that the use of computers to assist in the design process results in a trade-off between more successful solutions and a sense of satisfaction, creativity and agency.

Engineers grapple with complex design situations every day. ‘Optimising a technical system, whether it’s making it more usable or energy-efficient, is a very hard problem,’ said Antti Oulasvirta, a professor of electrical engineering at Aalto University and the Finnish Center for Artificial Intelligence.

Designers often rely on a mix of intuition, experience and trial and error to guide them. Besides being inefficient, this process can lead to ‘design fixation’, where designers lean towards familiar solutions while new avenues go unexplored. The ‘manual’ approach also typically won’t scale to larger design problems and is heavily reliant on individual skill.

The team tested an alternative, computer-assisted method that uses an algorithm to search through a design space, employing Bayesian optimisation, a machine-learning technique that both explores the design space and steers towards promising solutions. They hypothesised that a guided approach could yield better designs by scanning a broader swath of solutions and balancing out human inexperience and design fixation.

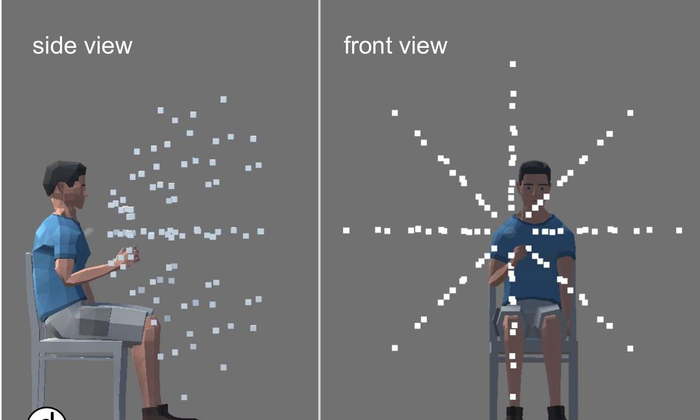

‘We put a Bayesian optimiser in the loop with a human, who would try a combination of parameters. The optimiser then suggests some other values and they proceed in a feedback loop. This is great for designing virtual reality interaction techniques,’ explained Oulasvirta. ‘What we didn’t know until now is how the user experiences this kind of optimisation-driven design approach.’

To find out, Oulasvirta’s team asked 40 novice designers to take part in their virtual reality experiment. The subjects had to find the best settings for mapping the location of their real hand holding a vibrating controller to a virtual hand seen in the headset.

Half of the designers were free to follow their own instincts in the process, while the other half were given optimiser-selected designs to evaluate. Both groups had to choose three final designs that would best capture accuracy and speed in the 3D virtual reality interaction task. Finally, subjects reported how confident and satisfied they were with the experience and how in control they felt over the process and the final designs.

The results were clear-cut. ‘Objectively, the optimiser helped designers find better solutions, but designers did not like being hand held and commanded – it destroyed their creativity and sense of agency,’ said Oulasvirta.

The optimiser-led process allowed the designers to explore more of the design space compared with the manual approach, leading to more diverse design solutions. The designers who worked with the optimiser also reported less mental demand and effort. However, this group also scored lower on expressiveness, agency and ownership when compared with the designers who did the experiment without a computer assistant.

‘There is definitely a trade-off,’ Oulasvirta continued. ‘With the optimiser, designers came up with better designs and covered a more extensive set of solutions with less effort. On the other hand, their creativity and sense of ownership of the outcomes was reduced.’

The experiment’s results are instructive when it comes to the development of AI that assists humans in decision-making. Oulasvirta suggested that people need to be engaged in tasks such as assisted design so that they retain a sense of control, don’t get bored and receive more insight into how a Bayesian optimiser or other AI is actually working.

‘We’ve seen that inexperienced designers especially can benefit from an AI boost when engaging in our design experiment,’ said Oulasvirta. ‘Our goal is that optimisation becomes truly interactive without compromising human agency.’